Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

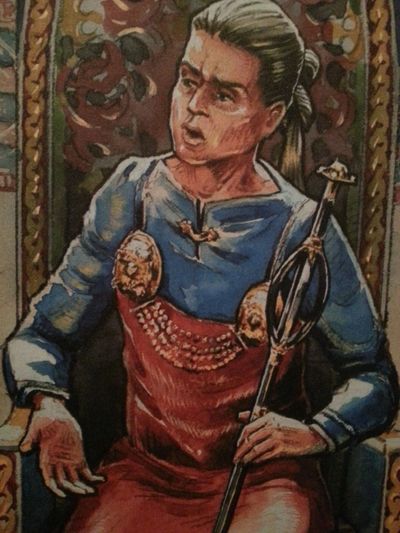

The Norns are known commonly as the weavers of fate, but in the Norse origin story, Voluspa, the three Norns "carve" or "score" fates (stanza 20, Trans. Bellows, 1936; Crawford, 2015). Is the association between Norns and weaving in primary sources as strong as commonly portrayed in modern arts and literature?

Associations between Norns and weaving in literary sources can be derived from interpretations of words, phrases, kennings, passages and metaphors, however, many of the key translations and interpretations are disputed. This article provides a brief overview of some of the stronger associations between Norns and weaving in old norse texts. The Norns are introduced in Voluspa (stanza 20) as follows:

Thence come the maidens | mighty in wisdom,

Three from the dwelling | down 'neath the tree;

Urth is one named, | Verthandi the next,--

On the wood they scored,-- | and Skuld the third.

Laws they made there, and life allotted

To the sons of men, and set their fates.

(Trans. Bellows, 1936)

Gylfaginning introduces the Norns as follows:

A hall stands there, fair, under the ash by the well, and out of that hall come three maids, who are called thus: Urdr, Verdandi, Skuld: these maids determine the period of men's lives: we call them Norns (stanza 15, Brodeur, 1916).

Brodeur translates the names of the Norns as Past, Present and Future. However, Byock (1998) translates their names as Fate, Becoming and Obligation.

Following skaldic metaphoric tradition, the Norns are directly associated with Valkyries, who in explicit ways, exhibit characteristics of the Norns themselves. The strongest evidence of this association is simply that the Norn, Skuld, herself is identified as both a Norn and a Valkyrie. Gylfaginning continues:

Valkyrs: them Odin sends to every battle; they determine men's feyness and award victory. Gudr and Róta and the youngest Norn, she who is called Skuld, ride ever to take the slain and decide fights (stanza 36).

Furthermore, both Norns and Valkyries are directly associated with swans. This literary connection to swans is significant because it informs interpretations of other passages associated with weaving. Swans may be read as a skaldic metaphor, linked primarily to the mythical home of the Norns, the Well of Udr. Gylfaginnig (stanza 16) tells that the Norns:

…dwell by the Well of Urd…” and “…two fowls are fed in Urdr's Well: they are called Swans, and from those fowls has come the race of birds which is so called.

In Volundarkvitha, Valkyr are recognized by their swan-feather clothing and are clearly depicted weaving:

Maids from the south | through Myrkwood flew,

Fair and young, | their fate to follow;

On the shore of the sea | to rest them they sat,

The maids of the south, | and flax they spun…

Swan-White second,-- | swan-feathers she wore…

(Stanzas 1 & 4. Trans. Bellows, 1936).

Similarly, Gardela (2009) follows Price (2002) and observes an association between Valkyries and seiðr in Darraðarljóð, “dated to the beginning of the tenth century… in which twelve valkyrjur weave a fabric of battle and thus shape human fate according to their will” (Gardela, 2009; pp: 69).

A passage in Helgakvita Hundingsbana (stanza 3) eludes more directly to Norns and weaving. The first line of the stanza in Old Norse text, “Sneru þær af afli örlögþáttu,” translates as directly as possible to, “they turned by force of fate” (author’s translation). The turning motion, along with references to threads” or “bands” in the third line of the stanza is perhaps the strongest direct link between Norns and weaving in Norse literary attestations, however, the passage is variously translated. Bellows (1936) translates the stanza as follows:

Mightily wove they the web of fate,

While Bralund's towns were trembling all;

And there the golden threads they wove,

And in the moon's hall fast they made them.

Crawford (2015) translates the same verse more ambiguously as:

They decided his fate with their power,

when they broke the walls of Bralund.

They had bands of gold;

they laid them down

under the night-time sky.

In Lokasenna (stanza 29), we learn that, "The fate of all | does Frigg know well, Though herself she says it not" (Trans. Bellows, 1936). In contemporary arts, the goddess Frigg is frequently portrayed as having a spinning wheel. But where in primary sources is Frigg's spinning wheel attested to? In Skaldskaparmal, Sturluson is careful to name the possessions of the Aesir and Asunjar, but does not mention Frigg's spinning wheel, nor any other weaving implements belonging to her. Her association with weaving can be inferred through metaphor and also cultural associations between weaving and womanhood, but direct literary associations are elusive.

Drawing from archaeological and literary evidence, Gardela (2009) concludes, “...evidence suggest that there was a clear relationship between the objects used in seiðr: they were all symbolically interlinked and revolved around the central concepts of spinning and weaving” (Gardela 2009, pp: 65). Weaving implements occur frequently in viking-age burials of women, including at least one woman identified as a seiðkanna. The National Museum of Denmark (2022) reports along with artifacts distinctive or seidr practice, including an iron rod and henbane seeds, "she had been given ordinary female gifts, like spindle whorls and scissors."

Seiðr’s close association with women and women’s activities is certain. In the Ynglinga Saga (stanza 7), seiðr is directly associated with ergi, which means ‘unmanliness’:

But after such witchcraft followed such weakness and anxiety, that it was not thought respectable for men to practise it; and therefore the priestesses were brought up in this art (Trans. Laing, 1844).

In Lokasenna (stanza 24), Loki accuses Odin of ergi, saying:

They say that with spells | in Samsey once

Like witches with charms didst thou work;

And in witch's guise | among men didst thou go;

Unmanly thy soul must seem

(Trans. Bellows, 1936)

Throughout the Icelandic Sagas, there are numerous attestations of males practicing various types of spell-craft characteristic of seiðr , especially Odin himself, wherein no suggestion of ergi can be detected. However, based on the above passages it stands that seiðr is literarily associated with women and with women’s societal roles.

Thus, a strong literary association between Norns and weaving can be derived from from ancient texts, however, this association is mainly inferred from complex metaphor. The significance of other craft associated with fate, including carving, allotting and turning fates, are also culturally significant, perhaps even unique to Norse culture, but are generally diminished in contemporary discussion compared to weaving. Indeed, the act of shaping fate seems to have taken many artistic forms, with weaving perhaps most central among them.

References

Gardela, L. (2009). The Good, the Bad and the Undead: New Thoughts on the Ambivalence of Old Norse Sorcery. Á Austrvega Saga and East Scandinavia. Papers from the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences. The 14th International Saga Conference , 1(14).

Sturluson, S. (1844). The Heimskringla: Or, Chronicle of the Kings of Norway. (Laing, S., Trans.) Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. (Original work circa 1275 )

Sturluson, S. (1936). The Poetic Edda. (Bellows, H. A. Trans.). Princeton University Press.

Sturluson, S. (2005). The Prose Edda: Norse Mythology. (Byock, J. L., Trans.). Penguin Books. (Original work circa 1272 CE)

Sturluson, S. (2015). Prose Edda Stories of the Norse Gods and Heroes. (Crawford, Jackson, Trans.). Hackett Publishing Company, Inc. (original work 1272 CE).

Copyright © 2024 Knowledge of the Old Ways - All Rights Reserved.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.